Scientific programme

FULL PROGRAMME AVAILABLE TO DOWNLOAD

The full programme is now available. You can download it by clicking below!

DETAILED PROGRAMME ONLINE

Discover now the detailed programme !

Explore our programme on Open Agenda, designed for a fluid and responsive experience on the phone, keeping you connected wherever you are.

INTERACTIVE PROGRAMME

Discover our interactive programme, laid out daily in a calendar format for a structured and immersive experience!

Discover the interactive programme

You can also download the programme for each day:

Programme as of the June 17.

Click on this banner to see the final list of Invited Talks in our online programme.

Cultural Programme

The CIHA Congress offers a series of Visits and Tours where you can discover the wealth of heritage, gastronomy and museums in Lyon, in the Lyon Metropole and in the Region Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes.

- Visits/Guided visits in Lyon and the Métropole of Lyon from June 23 to 28, 2024 (free registration)

- Tours (day and half-day) in the Auvergne Rhône-Alpes area on Friday 28 June, 2024 (paying registration)

The CIHA Congress offers also a programme of Events and Receptions from June 24 to 27, 2024.

The registration is closed.

TOURS

Architecture and Heritage of the Rhône, Couvent de La Tourette (Le Corbusier), Château de la Chaize

9:30 a.m. : Departure from Lyon

Couvent Sainte-Marie de la Tourette (Le Corbusier)

10:30 a.m. - 12:00 a.m. : Guided tour

12:30 p.m. - 1:30 p.m. : lunch on-site (single menu)

The Sainte-Marie de la Tourette Convent is currently home to a Dominican community of about ten people within a building designed by Le Corbusier and Yannis Xenakis. Built in 1956, this concrete structure is one of the architect’s most iconic works. The convent is conceived according to the three primary functions of monastic life: living, studying, and praying within simple and purified geometric volumes typical of the brutalist movement. Light plays a central role here thanks to ingenious transparency techniques with glass, openings towards the surrounding park, and other architectural perspectives. Nowadays, the place is shared between monastic life and openness to the public, who come to appreciate its architecture and contemporary art exhibitions presented throughout the year

Château de la Chaize

3:15 p.m. - 5:45 p.m. : Guided tour and wine tasting

Guided tour by Didier Repellin, chief architect of historic monuments

After lunch at the convent, a visit of the château de la Chaize offers an interesting example of the restoration of a historical monument from the 17 century. This vineyard estate was established in 1676 according to plans by Jules-Hardouin Mansart and André Le Nôtre, architects of Louis XIV. The building is in a classical 17th-century style, characterized by harmony and symmetry. The French garden offers a characteristic example of this period, the entirety of which has been classified as Historical Monuments since 1972.

Today, after being in the hands of François de La Chaize d’Aix's descendants for 350 years, the Gruy family has been overseeing the estate since 2017. Developing the vineyard activity towards organic and ecoresponsible production, the castle will offer the opportunity for congress participants to taste wines on-site. The restoration project will be presented by Didier Repellin, Inspector General of Historical Monuments and Chief Architect of Historical Monuments (honorary).

6:45 p.m. : Return to Lyon

Loire Architecture and Heritage, Firminy, Le Corbusier

9:00 a.m. : Departure from Lyon

Museum of Art and Industry, Saint-Etienne

10:30 a.m. - 12:00 a.m. : Guided tour

The journey begins with the exploration of the Museum of Art and Industry and the city of Saint-Etienne. This museum focuses its collections on three emblematic objects that illustrate the city’s history: weapons, textiles, and bicycles. This eclectic mix combines art and industry, the beautiful and the useful, form and function, coexisting within an innovative museography, housed in its 19th-century building. From military design to a ribbon collection, the world's first collection tracing the history of technological advancements in fashion, the museum aims to portray the material history and industrial creation through its regional heritage.

12:45 p.m. - 2:00 p.m. : Free lunch in Saint-Etienne

Le Corbusier site - Firminy-Vert

3:00 p.m. - 4:30 p.m. : Guided tour

The lunch break offers an opportunity to explore the city center of Saint- Etienne. The tour continues to the neighboring town of Firminy and the discovery of the Firminy-Vert neighborhood designed by Le Corbusier in the mid-1950s. In response to the exponential increase in the number of inhabitants and the unsanitary conditions of the city, the then-mayor Eugène Claudius-Petit proposed the idea of building a new neighborhood. This was to challenge the reputation of a place polluted by factory smoke, with the city being nicknamed “Firminy la Noire.” The birth of Firminy-Vert offered a new conception of urbanism, giving way to large green spaces and light. The atypical architecture of its housing unit and stadium is based on concrete work and the brutalist aesthetic reaches its peak with the recently completed conical-shaped church.

6:30 p.m. : Return to Lyon

Bresse Heritage

9:00 a.m. : Departure from Lyon

Royal Monastery of Brou

10:30 a.m. - 12:30 p.m. : Guided tour

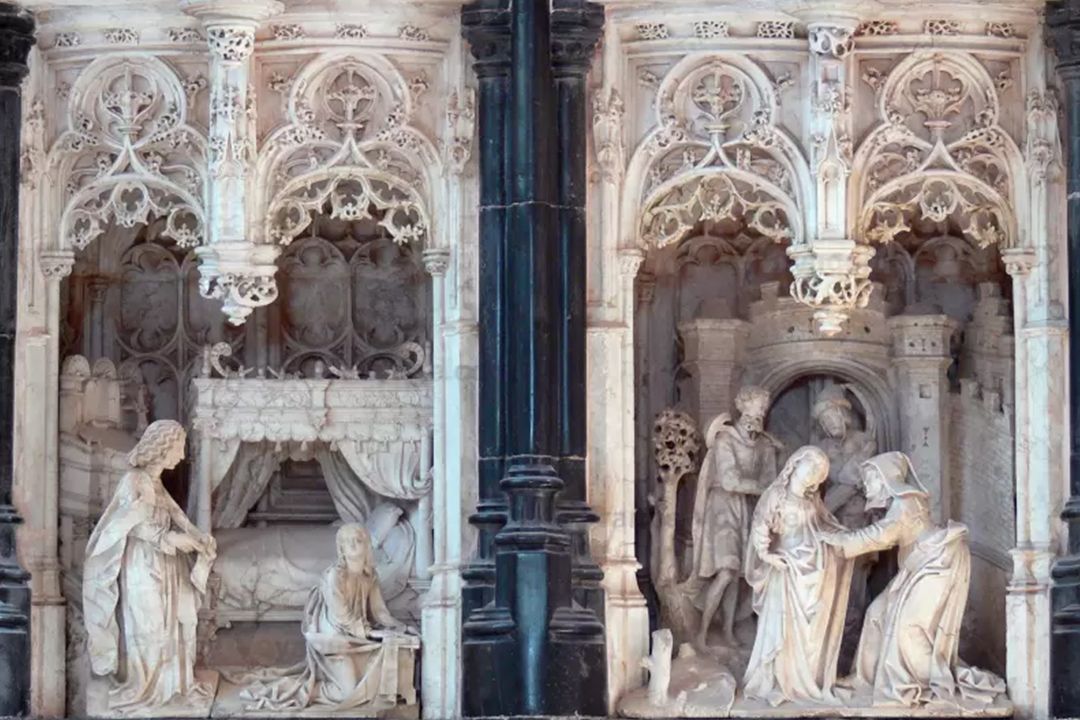

Built between 1506 and 1532, the Royal Monastery of Brou in Bourg-en-Bresse is a Gothic-style building with a unique history. Upon the death of her husband Philibert Le Beau three years after their union, Margaret of Austria had a monastery erected in the form of a mausoleum, housing the couple’s sumptuous tombs. The intricate carving work present throughout the architecture and the colorful lozenges typical of local roofing make it a unique place whose excellent state of preservation restores its original charm. The monastery was occupied by Augustinian monks until 1906, gradually losing its religious functions after the separation of Church and State. The main building now houses the municipal museum, which preserves collections ranging from medieval objects to decorative arts and contemporary pieces. Visitors will have the opportunity to visit the temporary exhibition Nicolas Boulard, la galerie des pains.

12:45 p.m. - 2:00 p.m. : Free lunch in Bourg en Bresse

Château de Fléchères

3:30 p.m. - 5:00 p.m. : Guided tour

After a leisurely lunch in the city center of Bourg-en-Bresse, the tour continues to the château de Fléchères. Built in the early 18 century, north of Lyon, this castle reflects the lives of the prominent figures of the Lyon region and the

splendor of these constructions symbolizing their influence. One such figure is Jean Sèves, a Calvinist who became one of the wealthiest men in the region, serving as regent of the Hospice de la Charité in Lyon and municipal magistrate after escaping the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. At the height of its grandeur, the castle was a means to assert his power and nobility. The place bears the traces of a troubled era, with its Calvinist temple located on the third floor, and the entirety of its frescoes painted by the Italian artist Pietro Ricchi.

6:30 p.m. : Return to Lyon

Heritage and Restoration in Givors

9:30 a.m. : Departure from Lyon

Curch of Saint-Nicolas

10:30 a.m. - 12:00 a.m. : Guided tour

The morning visit takes place at the stained-glass restoration site of the Church of Saint Nicolas, one of the three major churches in Givors. Its uniqueness lies in the characteristic eclectic style of the 19th century, drawing from Greco-Latin, neo- Gothic, and even Byzantine forms. The region's glasswork specialty is evident in the intricately detailed stained-glass windows, showcasing particular craftsmanship. The organ, built in 1865 by Joseph Merklin's workshops in Paris, has been classified as a Historical Monument since 1986.

12:30 p.m. - 2:00 p.m. : Group lunch at the Brasserie du Fleuve in Givors (free menu - lunch not included in the excursion‘s fee)

Jean Renaudie’s Cité des Étoiles and urban heritages of Givors

3:30 p.m. - 5:00 p.m. : Guided tour

Lunch provides an opportunity to explore the city center of Givors. The afternoon is dedicated to visiting the Cité des Étoiles neighborhood, designed by French architect Jean Renaudie. Built between 1974 and 1981, this housing complex is located in a unique place, the Saint Gérald hill. This natural location became one of the architect's concerns, fueling his desire to balance housing and nature. The Cité des Étoiles embodies a renewal in urban planning at the time, in agreement with the municipality of the city, led by the communist mayor Camille Vallin. The place is an example of political will aiming to improve the daily lives of residents through adapted and innovative architecture.

6:30 p.m. : Return to Lyon

Museums and Restoration in Grenoble

8:30 a.m. : Departure from Lyon

ARC NUCLEART restoration workshop

10:30 a.m. - 12:00 a.m. : Guided tour

The morning begins with a visit of the ARC-Nucléart restoration workshop, a laboratory located in the city’s scientific polygon. Its missions include ensuring the conservation and restoration of objects made of organic materials (wood, leather, fibers) by exposure to gamma radiation. This laboratory develops new treatment methods for degraded materials. It has enabled the restoration of numerous objects found in the region, such as a seven-meter-long Carolingian dugout canoe, recovered in 2017 from Lake Bourget and now on display at the Savoy Museum in Chambéry. The visit must follow a protocol for safety reasons.

12:30 p.m. - 1:45 p.m. : Free lunch in Grenoble

Grenoble Museum

2:00 p.m. - 3:30 p.m. : Guided tour

After a lunch break allowing exploration of the city center of Grenoble, the afternoon is dedicated to visiting the Grenoble Museum. Created in 1798 under the impetus of revolutionary events, the museum offers an overview of regional, national, and international visual arts from antiquity to present day. The visit to the temporary exhibition Miró. A Blaze of Signs in partnership with the Pompidou Center and the reserves allows for a perspective on conservation and restoration issues within the museum.

Musée de l’Évêché

3:45 p.m. - 5:00 p.m. : Guided tour

The day continues with a tour of the Musée de l’Évêché located in the 13th-century Bishop's Palace. Laden with history, this historic building has harmoniously integrated contemporary reorganization, with the use of glass, steel, and concrete. It now houses the permanent exhibition Isère in History, which covers the history of the region from prehistory to the 20 century. The museum's basement hosts the archaeological remains of the baptistery (3rd - 4th centuries), testimony to the religious history of the early Christian times.

7:00 p.m. : Return to Lyon

Art and Museum in Grenoble

8:30 a.m. : Departure from Lyon

Le Magasin, National Center for Contemporary Art

11:00 a.m. - 12:30 p.m. : Guided tour

During the morning, the excursion stops at the National Center for Contemporary Art in Grenoble, also known as Le Magasin. Inaugurated in 1986, this exhibition space is housed in a hall built at the beginning of the 20th century in the Eiffel workshops for the 1900 Universal Exhibition in Paris. One of the first national centers for contemporary art in France, the space is divided between several temporary exhibitions organized in collaboration with artists. Since 1987, one of the missions of this art center has been to offer curatorial training through the École du Magasin. The visit will focus on the exhibition DROP by Robberto & Milena Atzori.

12:45 p.m. - 1:45 p.m. : Free lunch in Grenoble

Grenoble Museum

2:00 p.m. - 3:30 p.m. : Guided tour

After a lunch break allowing exploration of the city center of Grenoble, the afternoon is dedicated to visiting the Grenoble Museum. Created in 1798 under the impetus of revolutionary events, the museum offers an overview of regional, national, and international visual arts from antiquity to present day. The visit to the temporary exhibition Miró. A Blaze of Signs in partnership with the Pompidou Center and the reserves allows for a perspective on conservation and restoration issues within the museum.

Hébert Museum

3:45 p.m. - 4:45 p.m. : Guided tour

The day continues with a visit of the Hébert Museum, the home of French painter Ernest Hébert associated with late 19th-century art. In this wooded estate of almost two hectares, the intimate

atmosphere of the house highlights the memories of the painter’s life. Since its opening in 1979, the museum has had a dual focus: to promote a better understanding of art from this period and to confront it with the practice of contemporary artists, whether young or established. Two exhibitions are presented during this visit : Clothing & Elegance. 1800-1900 which invites visitors to delve into the evolution of fashion from the past to the present day, and Denis Rouvre. Photographs, which offers a critical view of our consumption habits through clothing.

7:00 p.m. : Return to Lyon

Museums in Drôme-Ardèche

9:00 a.m. : Departure from Lyon

Moly-Sabata Museum/A. Gleizes Foundation, Sablons

10:30 a.m. - 12:00 p.m. : Guided tour

The morning visit takes place in Sablons, a small village in Ardèche, where Cubist painters Albert Gleizes and Juliette Roche-Gleizes established the oldest active artists' residence in France, starting in 1927. Moly-Sabata is the name that the couple gave to this hospitality venue located in an 18th-century mansion. After the couple's death, the place was bequeathed to the Artists’ Foundation, which ensures two main missions: the recognition and dissemination of Albert Gleizes’ work, and the support of contemporary artists welcomed in the Moly-Sabata workshops. These two missions are at the heart of the visit, with the exhibition of Albert Gleizes’ studio collection and the work of Juliette Roche’s and of the ceramicist Anne Dangar, a disciple of the Cubist painter.

12:45 p.m. - 1:45 p.m. : Free lunch in the Fondation’s Park (picnic to bring)

Palais Idéal du Facteur Cheval, Hauterives

2:30 p.m. - 4:00 p.m. : Guided tour

After a lunch break in the Foundation's park, the afternoon is dedicated to the visit of the architectural masterpiece erected by Ferdinand Cheval in Hauterives, Drôme. In 1879, at the age of 43, he stumbled upon a strange stone during his rounds as a postman in his village, and came up with the idea of a monument building. According to legend, the postman Cheval spent thirty-three years of his life building his Ideal Palace. Inspired by nature and the postcards passing through his hands, the palace was built with the stones he collected daily. Completed in 1912, this extraordinary palace followed no architectural rules or artistic movements. André Malraux initiated its Monument Historic classification in 1969 under the title of “naive art.” The palace’s legacy is ensured by the imagination it nurtures, that of surrealists like Max Ernst and his painting Facteur Cheval (1932).

6:00 p.m. : Return to Lyon

Heritage of Le Puy-en-Velay

8:30 a.m. : Departure from Lyon

Cloister and Cathedral complex of Le Puy-en-Velay

10:45 a.m. - 12:30 p.m. : Guided tour

The journey begins with a guided tour of the cloister and the cathedral complex of Le Puy-en-Velay. The Romanesque buildings are famous for their polychrome arcades, adorned with a mosaic of white, red, and black lozenges, and their historiated capitals. Perched on a volcanic mound, the complex is notably one of the stops on the routes of the Way of Saint James.

12:30 p.m. - 2:00 p.m. : Free lunch in Le Puy-en-Velay

Urban heritage of Le Puy-en-Velay

2:00 p.m. - 3:30 p.m. : Guided tour

After a lunch break in the historic center of the city, the afternoon is dedicated to the visit of the urban heritage of Le Puy-en-Velay, a millennium-old city whose Gallo-Roman origins, popularized since the early centuries of Christianity by the dedication to the Virgin Mary, mark the starting point of the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. The city center is now a preserved historic sector covering thirty-five hectares. It includes the Notre-Dame Cathedral and the Hôtel-Dieu, both UNESCO World Heritage sites, and is enhanced by lively or digital scenography, which artfully tell the stories of the past.

6:00 p.m. : Return to Lyon

Guided Visits

Discover the Cultural programme of visits in Lyon and the Métropole of Lyon from June 24 to 28, 2024 : guided visits and free visits in museums, art and architecture centres, historical sites, art foundations,etc.

-

Museums - Art and architecture centres

Access to all Lyon municipal museums is free on presentation of the CIHA 2024 Pass for the duration of the congress : Musée des Beaux-Arts, Musée d’Art Contemporain, Musée de l’Imprimerie et de la Communication Graphique, Musées Gadagne, Centre d'Histoire de la Résistance et de la Déportation, Musée de l’automobile Henri Malartre

- Musée des Beaux-Arts of Lyon

- Lyon Museum of Contemporary Art

- Gadagne Museum

- Lugdunum - Museum and Roman theatres

- Tony Garnier Urban Museum

- Archipel, a centre for urban culture

- BF15

- Musée des Confluences

- Lyon Museum of Fabrics and Decorative Arts

- Museum of Printing and Graphic Communication

- Villeurbanne Institute of Contemporary Art

- Musée des Moulages

-

Musée des Beaux-Arts of Lyon

20, place des Terreaux, 69001 Lyon

| Musée des Beaux Arts (mba-lyon.fr)

Closed on Tuesdays

Opening hours : 10h00-18h00

The museum is located in the heart of Lyon's Presqu'île district, in the setting of a 17th-century abbey and its cloister, now a sculpture garden. The museum's encyclopaedic collections are organised into five departments covering a panorama of the great civilisations and schools of art from Antiquity to the present day. In association with the CIHA, the temporary exhibition Connecting Worlds will put the challenges of the congress into perspective through the history of exchanges and interconnections in the age of globalisation.

-

Lyon Museum of Contemporary Art

Cité Internationale, 81 Quai Charles de Gaulle, 69006 Lyon

| Musée d'art contemporain (mac-lyon.com)

Fermé le lundi et mardi

Opening hours : 11h00-18h00

Located in the Cité Internationale since 1995, the museum presents national and international art in all its forms. The macLYON collection includes over 1,400 works in a wide variety of forms, materials and sizes, as well as monumental and immersive installations, some of which are acquisitions from the Lyon Biennial of Contemporary Art, created in 1991. Three temporary exhibitions will also be on show: Friends in Love and War - L'Éloge des meilleurs-es ennemi-es presents a selection of works from the British Council and macLYON collections on the theme of friendship; Désordres is from the Antoine de Galbert collection; and River of no Return is a solo exhibition by the artist Sylvie Selig.

-

Gadagne Museum

1 Place du Petit Collège, 69005 Lyon

Gadagne | Gadagne et ses deux musées (gadagne-lyon.fr)

Closed on Mondays and Tuesdays

Opening hours : 10h30-18h00

The Hôtel de Gadagne is one of the key sites in Lyon's heritage and Old Lyon, emblematic of its historic district, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Gadagne complex is a magnificent Renaissance building that houses two museums: the Musée d'Histoire de Lyon and the Musée des Arts de la Marionnette. The exhibitions retrace the history of the capital of Gaul right up to the 21st century, from an urban planning, economic, social, political and cultural perspective.

-

Lugdunum - Museum and Roman theatres

17 Rue Cleberg, 69005 Lyon

Accueil - Lugdunum Musée et théâtres romains (grandlyon.com)

Closed on Mondays

Opening times: 11am-6pm

The museum and theatres are located on the slopes of Fourvière hill, on the site where the Roman city of Lugdunum was founded in the 1st century BC. Almost invisible from the outside, the museum, created in the 1970s, blends into the landscape, which is made up of two monuments: a theatre and an odeon, both part of the UNESCO World Heritage site. The museum has one of the richest archaeological collections in France, and traces the town planning, army and currency, religions and circus games of this period.

-

Tony Garnier Urban Museum

4 Rue des Serpollières, 69008 Lyon

Closed on Sunday and Monday

Opening times : 14h00-18h00

Built by architect Tony Garnier between 1920 and 1933, the Cité Tony Garnier offers an open-air tour of the nineteen giant murals and six frescoes designed by foreign artists and sponsored by UNESCO. The museum has a 1930s flat museum and an exhibition space.

-

Archipel, a centre for urban culture

21 Pl. des Terreaux, 69001 Lyon

Archipel Centre De Culture Urbaine (archipel-librairie.fr)

Closed on Mondays

Opening hours : 13h00-19h00

Archipel is made up of the association La Maison de l'architecture Rhône-Alpes and an independent specialist bookshop. They share a common ambition: to raise public awareness of contemporary forms of architecture through a rich programme of exhibitions, conferences and workshops.

-

BF15

11 Quai de la Pêcherie, 69001 Lyon

La BF15 - Espace d'art contemporain >>> Lyon >>> France

Closed on Sunday, Monday and Tuesday

Opening hours : 14h00-19h00

The BF15 is a contemporary art space that presents artistic works that question our contemporary world, in particular the place and role of art in our society. Encouraging emerging approaches, it promotes reflection, artistic research and experimentation. From 07 June to 27 July, the exhibition As an owl in the daylight by Tristan Chignal- d'Argent will be on show, in partnership with the Fondation Albert Gleize de Molly-Sabata and as part of the Printemps du Dessin programme.

-

Musée des Confluences

86 Quai Perrache, 69002 Lyon,

Open every day

Opening hours : 10h30-18h30

Admission charged according to current price list

Visit 1. [FULL / Booking no more available]

Guided tour: Friday 28 June, 2.00 pm - 3.30 pm.

Capacity: 25 people

Opened in 2014, the Musée des Confluences is the heir to collections spanning five centuries of history. The museum's permanent displays evoke the great story of humankind in four distinct exhibitions that bring together the sciences to explore the history of life and humankind. It looks at the origins and future of humankind, the diversity of cultures, and the place of humans within the living world. The 3.5 million objects in the museum's collections represent a major collection in the natural, human and technical sciences, drawn from museums that no longer exist (the Muséum d'Histoire Naturelle and the Musée Guimet in Lyon). The temporary exhibitions À nos amours, Secrets de la Terre and Épidémies, prendre soin du vivant (Epidemics, caring for the living) will echo the themes of the CIHA and the visit devoted to ‘Matière à récits’ (Storytelling Matter), in the permanent tour of the collections.

-

Lyon Museum of Fabrics and Decorative Arts

Visit 2. [FULL / Booking no more available]

Guided tour: Tuesday 25 June, 11am-12.30pm.

Due to the temporary closure of the museum for renovation work, the site is now located in Unieux, accessible by TER train (20-minute walk from the site).

Capacity: 25 people

The museum has the largest collection of textiles in the world, with over 2 million items covering 4,500 years of textile production, and one of the finest collections of decorative arts in France. Housed in two mansions built in the 18th century on Lyon's Presqu'île, the museum is currently closed for renovation, with reopening scheduled for 2028. The museum's cultural programme continues with events and off-site exhibitions. The visit will focus on works taken out of storage for the occasion.

-

Museum of Printing and Graphic Communication

13 Rue de la Poulaillerie, 69002 Lyon

Closed on Monday and Tuesday

Opening hours : 10h30-18h00

Visit 3. [FULL / Booking no more available]

Guided tour: Monday 24 June, 10.00am-11.30am, the tour will be in French, with labels in English.

Capacity: 25 people

Created in 1964, the museum celebrates the early days of printing from the end of the 15th century to the middle of the 16th century, when Lyon was the epicentre of innovation and the spread of the printed book. The city continues to play a leading role in the spread of innovative techniques such as photocomposition. The museum's tour will take in five centuries of graphic development, and explore new horizons through Le Musée Ambulant. Readings by Miyazaki, a temporary exhibition by the Japanese artist.

-

Villeurbanne Institute of Contemporary Art

11 Rue Dr Dolard, 69100 Villeurbanne

IAC — Institut d’art contemporain — Villeurbanne/Rhône-Alpes (i-ac.eu)

Closed on Monday and Tuesday

Opening hours: 2pm-6pm and 1pm-7pm at weekends

Visit 4. [FULL / Booking no more available]

Visit: Friday 28 June, 10am-12pm, presentation of the Espace Cerveau Laboratory and exhibitions.

Capacity: 30 people

The art centre was created in 1997 from the merger of the Nouveau Musée, a contemporary art centre founded in 1978, and the Fonds régional d'Art Contemporain Rhône-Alpes, founded in 1982. As a creative and research tool for contemporary art, the Institut organises exhibitions and meetings, and is building up a collection of works of international renown. At the same time, it is developing the Brain Space Laboratory, which contributes to the development of interdisciplinary research linking art to neuroscience, astrophysics and new technologies on a global scale. The temporary exhibition Cosmomorphic practices - (Re)generating the living will have a direct bearing on the issues of materiality and immateriality.

Visite 21.

Wednesday 26 June

18:00-20:00

Capacity: 15 peopleA conversation with Dane Mitchell about the work Aeromancy (Sketches of Meteorological Phenomena) in the current exhibition Pratiques cosmomorphes - (Ré)générer le vivant.

Pared down and sober, Dane Mitchell's works are the result of capturing and fixing fleeting organic substances. He plays on scientific principles to distance our discernment and spark our imagination. Drawing on his work Aeromancy (Sketches of Meteorological Phenomena) (2024-2017), Dane Mitchell will explore his relationship with matter, the invisible and the ties that bind us to the world.

-

Musée des Moulages

87 Cours Gambetta, 69003 Lyon

Musée des Moulages - Université Lumière Lyon 2 (univ-lyon2.fr)

Closed from Sunday to Tuesday

Opening hours : 14h00-18h00

Visit 5. [FULL / Booking no more available]

"Material history of the Musée des Moulages collections"

Guided tours: Tuesday 25 June, 6.00 pm, 6.30 pm and 7.00 pm, duration 1 hour, limited to 20 people per tour. Tours in English available. Museum closes at 9pm.

Capacity: 25 people

Inaugurated in 1899 as part of the University of Lyon, the museum is now housed in a former industrial building in the 3rd arrondissement. Dedicated to the teaching of art history and archaeology, it has become a place for the mediation and dissemination of artistic knowledge. Its collection includes almost 2,000 plaster casts, 300 archaeological objects and tens of thousands of photographs, reflecting the development of Western sculpture from Archaic Greece to the 19th century. To date, some fifty sculptures have been restored, the most recent being the print of Paradise Gate. The tour will look at the materiality of these casts, their observation and restoration, as well as the manufacturing techniques, the special treatment of the surfaces, the fragility of the plaster and the marks of their century-long use in a humanities and social sciences university.

-

Art Foundations

-

Bullukian Foundation

26 Place Bellecour, 69002 Lyon

Closed on Sunday and Monday

Opening hours : 14h00-18h00

Visit 6.

Guided tours:

*Tuesday 25 June, 2.00 pm - 3.00 pm, with the artist Nicolas Daubanes and the three curators of the H(H)istoires exhibition [This visit is FULL / Booking no more available]

*Friday 28 at 10.00 am.

Capacity: 30 people

Named after Napoléon Bullukian (1905-1984), a French resistance fighter and industrialist, the Bullukian Foundation has been committed to and active on a daily basis since 1985 in three areas: support for contemporary art, applied medical research and the promotion of Armenia. The Foundation houses an open-air contemporary art centre and offers temporary exhibitions, meetings and outreach activities to encourage creation, experimentation and access to art for all audiences. The temporary exhibitions Arménie, les temps du sacré by artist Pascal Convert and the group exhibition H(H)istoires consider the place, in the collective memory, of the destruction of works of world heritage and the place of the Armenian genocide.

-

Collection Tomaselli

22 Rue Laure Diebold, 69009 Lyon

Closed on Sunday and Monday

Opening hours : 10h30-17h30

Visit 7. [FULL / Booking no more available]

Guided tour: Tuesday 25 June at 6pm. The tour will be followed by a cocktail reception at 7pm (to be confirmed).

Capacity: 25 people

Open to the public since November 2022, Mr Jérôme Tomaselli's private collection focuses on the arts in Lyon, representative of the different periods in the history of art. The exhibition of regional works, some of which are little-known, provides an opportunity to discover artists who were born, lived and worked in Lyon, or who studied at the city's École des Beaux-Arts. The temporary exhibition Modernity in Lyon: 1900-1925 will explore the relationships between artists and their links with other cities such as Paris and Rome, through the effervescence of the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century.

-

Musée l'Organe. The Abode of Chaos

17 Rue de la République, 69270 Saint-Romain-au-Mont-d'Or

La Demeure du Chaos – Musée d'Art Contemporain de Lyon

Visit 8.

Guided visits: Wednesday 26 June from 6.30pm and all evening long. Cocktail reception at 8pm.

Capacity for the evening: 200 people (see Events and Evenings)

La Demeure du Chaos is an alternative art project launched by Thierry Ehrmann in 1999. Located in the village of Saint-Romain-au-Mont-d'Or, near Lyon, it officially opened its doors to the public in 2006. The museum has the appearance of a vast post-apocalyptic setting, featuring a number of installations that explore the current issues in contemporary art, relating to the legitimacy of creation, the status of works of art and their future. The museum also houses the activities and documentary resources of Artprice, a website devoted to art market quotations.

-

Fondation Renaud Fort de Vaise

27 Boulevard Saint-Exupéry, 69009 Lyon

Fort de Vaise – Fondation Renaud (fondation-renaud.com)

Closed Monday and Tuesday

Opening hours : 14h00-18h00

Visit 9. [FULL / Booking no more available]

Guided tour: Tuesday 24 June, 17:30-19:00.

Capacity: 25 people

Created in 1994, the Fondation Renaud is the result of the Renaud family's desire to showcase its collections and heritage sites to the people of Lyon. It now houses 8,000 objects and works of art, notably by 19th and 20th century Lyonnais painters. The museum's mission is to support contemporary art, organise artists' residencies and promote Lyon's heritage. The temporary exhibition by the artist Lucas Zambon will provide an opportunity to showcase the work of this multi-disciplinary artist in residence at the foundation.

-

URDLA

207 Rue Francis de Pressensé, 69100 Villeurbanne

URDLA | Expositions, Oeuvres & Artistes

Closed on Sunday and Monday

Opening hours : 10h00-18h00

Visit 10. [FULL / Booking no more available]

Guided tour: Friday 28 June, 14:00-15:30. A free guided tour of the exhibition room and printing workshop, with English translation provided.

Capacity: 25 people

Located in a renovated former factory, the Union régionale pour le développement de la lithographie d'art (regional union for the development of art lithography) presents the workings of lithographic presses, witness to the work involved in making images, often in contrast to today's digital techniques. Created in 1978 on the initiative of painter Max Schoendorff, the centre includes an art gallery and hosts residencies for artists working in traditional printmaking.

-

ARTISSIMA

Private collection of contemporary art

Le Moulin

673, chemin de la Plage

69270 Rochetaillée sur SaôneGuided visits:

The collection can be visited exclusively by reservation during guided tours lasting an hour and a half. Please do not hesitate to contact us to organize group visits for groups of 10 or more.

The ARTISSIMA Collection is the private collection of contemporary art of François and Michelle Philippon.

François Philippon is a collector of contemporary art; he has been searching, discovering and buying works for over 40 years. Michelle has always supported this project and has been very committed to the opening of the Moulin, a private space that houses this collection of paintings and sculptures, but also photographs, drawings, videos and other installations by international artists.

The ARTISSIMA Collection is the story of a private passion, started at a very young age. It is not a family story, but the passion of a life, intimate, discreet and constant over the years.

From Paris, then quickly from Lyon, acquisitions are made "with the head and the heart", mainly from galleries, in France and abroad. The ARTISSIMA Collection has been built in freedom and exigency, around a deep love for art, the sensitivity of artists and their place in the history of their time. The choices are mainly focused on themes such as fragility, rupture, construction/deconstruction.

This collection reflects the journey of a man who today assumes this passion to the point of being able to propose this very personal place, which resembles a museum without being one. In this private place, which is not subject to the constraints of a museum, there is a real desire for freedom, sharing and transmission.

-

-

Architectural heritage

-

Jacobins District

Visit 11. [FULL / Booking no more available]

Guided tour: Friday 28 June, 10am-11.30am, by Véronique Belle, Researcher, General Inventory and Cultural Heritage, Department of Culture and Heritage.

Capacity: 15 peopleThe tour takes in the Jacobins district, home to the former Jacobins convent, destroyed in 1808, and the historic buildings of the 17th and 18th centuries on Lyon's Presqu'île.

-

Lyon's heritage. Perrache district

73-75 rue President, Edouard Herriot 69002 Lyon: meet at the entrance to the Hôtel Mercure

Visit 12. [FULL / Booking no more available]

Guided tour: Friday 28 June, 15:30-17:00, by Véronique Belle, researcher, Inventaire général et Patrimoine culturel, Direction de la Culture et du Patrimoine.

Capacity: 15 peopleThe tour will include a visit to the Hôtel Mercure, an architectural heritage with Art Nouveau decor that has remained intact. The tour continues with a visit to La Brasserie Georges, an emblematic restaurant founded in 1836, whose Art Deco decor is complemented by paintings by Lyon artist Bruno Guillermin.

-

Cornwall water plant and pump

Adress: Meet at the Salle Cornouailles - Ancienne usine des eaux 2 avenue de Poumeyrol 69300 Caluire

Visit 13. [FULL / Booking no more available]

Guided tour: Wednesday 26 June, 12.30-14.00, by Nadine Halitim-Dubois, Researcher, General Inventory and Cultural Heritage, Department of Culture and Heritage.

Capacity: 15 people

The tour is devoted to the Saint-Clair waterworks, which dates from 1854 and, with its 3,800 m2 of underground basins, period buildings and the Cornouailles pump from Lyon, is a rare example of industrial heritage still visible. The site, which is closed to the public, is located on the other side of the Rhône, opposite the Palais des Congrès.

-

The Grand Hôtel-Dieu and the Chapel

Place de l'Hôpital, in front of the Chapelle, 69002 Lyon

Visit 14.

Guided tour :

Capacity: 25 people

Located in the Hôtel-Dieu, Lyon's former hospital, the Chapel, built in the 7th century and then restored in the 19th century, was the baptismal font for many children born at the Hôtel-Dieu, before gradually falling into oblivion. Its restoration, undertaken in 2012 by the Hospices Civils de Lyon, is now a chance to rediscover its Baroque architecture, the wealth of its paintings and sculptures, and the trompe-l'œil painted decoration that covers its entire walls and vaults.

-

Urban tour in Villeurbanne

Address: Hôtel de Ville (Mairie) de Villeurbanne, Place du Dr Lazare Goujon, 69100 Villeurbanne

Visit 15.Guided tour: Friday 28 June, 14:00-16:00, by Stéphane Frioux, lecturer in contemporary history at Université Lymière Lyon 2, and Vincent Veschambre, director of Le RIZE (Cultural Centre in Villeurbanne). Meeting point: Hôtel de Ville (Mairie) de Villeurbanne, Place du Dr Lazare Goujon, 69100 Villeurbanne

Capacity: 25 people

Visit 15bis.

The tour will be preceded by a cocktail reception at 12:00 at the City Hall of Villeurbanne ; Wedding hall.

Capacity : 70 people

The tour explores the history of the city of Villeurbanne, whose historic skyscraper centre is a unique architectural ensemble, built between 1927 and 1934. Blending social housing and working-class housing with a modernist style inspired by Europe and North America, the tour includes a visit to a show flat from the period, where you can appreciate the solutions introduced to provide modern comfort.

-

The Hearing Matter Route

14 Av. Berthelot, 69007 Lyon : meet at the Maison des Sciences de l'Homme

Visit 16. [FULL / Booking no more available]

Guided tour: Thursday 27 June, 10.00am-10.30am and 10.30am-11.00am, by Mylène Pardoen, research engineer - IR (CNRS), archaeologist of the soundscape.

Capacity: 8 people

This presentation offers an opportunity to hear the material and the history, the environment and the activities that took place during the various phases of the construction work around Notre-Dame de Paris. The aim is to immerse ourselves in the sensoriality of the past, to rediscover the gestures and practices of the past, and to record them. The session is divided into two parts: a presentation of the archaeology of sound heritage and its methodology, linked to the ESPHAISTOSS project (Study and analysis of the sensoriality of craft and heritage trades), and immersive listening to a sound reconstruction in the eponymous room at the MSH.

-

-

Old Lyon (Renaissance, 18th and 19th c.)

-

Saint-Jean Cathedral and traboules

Visit 17. [FULL / Booking no more available]

Guided tour: Tuesday 26 June at 5.00 pm, by Nathalie Mathian, lecturer in the history of modern art, Université Lyon 2

Adress: in front of Saint-Jean cathedralCapacity: 5 people

Thanks to the combined efforts of the State, the City of Lyon and local residents' associations, Vieux Lyon became France's first ‘protected area’ in 1964. The district was subsequently listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1998. The tour includes visits to Saint-Jean Cathedral, a Gothic and Romanesque church, and the famous Renaissance-style traboules of Vieux Lyon.

-

-

Lyon Silk industries

-

Association Soieries vivantes

Atelier Municipal de Passementerie, 21 Rue Richan, 69004 Lyon

Association Soierie Vivante (soierie-vivante.asso.fr)

Closed on Sunday and Monday

Opening hours: 9.00am - 12.00pm / 1.30pm - 6.00pm

Visit 18.

Guided tour: Friday, June 28, 2 p.m. - 4 p.m.

Admission charge: 7€

Capacity: 25 peopleThe Soierie Vivante association is made up of historians, Lyonnais textile professionals and local enthusiasts. It explains the history and operation of the hand-weaving looms, equipped with Jacquard cartons dating from 1830, all of which have been listed as historic monuments thanks to the association's support. The association also provides guided tours and demonstrations of the looms for the general public.

-

Maison des Canuts

10 Rue d'Ivry, 69004 Lyon

Maison des Canuts • Musée de la soie de Lyon • Croix-Rousse

Closed on Sunday and Monday

Opening hours : 10.00-13.00 / 14.00- 18.00

Visit 19.

Guided tour: Friday, June 28, 10:00 - 12:00

Admission charge: 11€

Capacity: 25 peopleCreated in 1970 by the weaving cooperative, the Maison des Canuts housed the headquarters of the Syndicat des Tisseurs et Similaires in the 19th century. Located in the historic Croix-Rousse district, the Maison des Canuts invites visitors to discover the history of Lyon's silk industry, through a tour that traces the origins of silk, the manufacture of gold and silver threads, the organisation of the silk trade in Lyon and the Canuts' revolts.

-

The Villas Tony Garnier trail in Saint-Rambert

Visit 20.

Address: meet in front of Tony Garnier's villa, at the corner of Quai Paul-Sédaillan and rue de la Mignonne, Lyon, 69009.

Capacity: 15 people [FULL / Booking no more available]

Guided tour: Wednesday 26 June, 9am-12.30pm, by Pierre Gras, Honorary Professor at the École nationale d'architecture de Lyon.

Between 1910 and 1920, Tony Garnier built three villas on the Saint-Rambert site, on the banks of the Saône. The first was for himself, the second for his wife and the third for a private client, Antoinette Bachelard. These three buildings are among the pioneers of the Modern Movement, offering a different perspective on its beginnings. Their construction and decoration are particularly interesting for their materiality. The first two are artists' homes, and are sensitive and seminal testimonies to the movement. The owners of these villas have agreed to welcome a limited number of visitors. Their visit is an exceptional opportunity.

-

-

Art Galleries in Lyon

-

Françoise Besson Gallery

Galerie Françoise Besson — Galerie Lyon (francoisebesson.com)

10 Rue de Crimée, 69001 Lyon

Closed on Sunday, Monday and Tuesday

Opening hours : 14h30- 19h00

Visit 21.

Guided tour : from Wednesday to Saturday, 14:30-19:00

Capacity: 15 people

No registration required -

Regard Sud Gallery

Regard Sud | Galerie d'art contemporain

1/3 Rue des Pierres Plantées, 69001 Lyon

Closed on Sunday and Monday

Opening hours : 14h00 - 19h00

Visit 22.

Guided tour : from Tuesday to Saturday, 14:00-19:00

Exhibition : Resting on the course of the sky by painter Lilian Euzéby.

Capacity: 15 people

No registration required

-

Le Réverbère gallery

Galerie le reverbere / Accueil

38 Rue Burdeau, 69001 Lyon

Closed from Sunday to Tuesday

Opening hours : 14h00- 19h00

Visit 23.

Guided tour : from Wednesday to Saturday, 14:00-19:00

Exhibition: Silence by Julien Magre.

Capacity: 15 people

No registration required

-

L’Œil écoute

Galerie l'Oeil Ecoute | Vieux Lyon (galerie-oeil-ecoute.fr)

3 Quai Romain Rolland, 69005 Lyon

Closed from Monday to Thursday

Opening hours : 14h00- 19h00

Visit 25.

Details to come

-

Ceysson & Bénétière gallery

Expositions - Max Charvolen Lyon - Ceysson & Bénétière (ceyssonbenetiere.com)

21 Rue Longue, 69001 Lyon

Closed on Sunday and Monday

Opening hours : 11h00-18h00

Visit 24.

Visite guidée: From Tuesday to Saturday, 11:00 - 18:00

Capacity: 15 people

No registration required -

Ories gallery

33 Rue Auguste Comte, 69002 Lyon

Closed on Sunday and Monday

Opening hours : 15h00- 19h00

Visit 27.

Details to come

-

Tatiss gallery

35 rue Auguste Comte 69002 Lyon

galerie tatiss - galerie d'art contemporain à lyon

Closed from Sunday to Tuesday

Opening hours : 14h00- 19h00

Visit 25.

Guided tour: From Wednesday to Friday 2pm-7pm and Saturday 10.30am-7pm

Exhibition: Le terrain du vague by artist Sarah Krespin

Capacity: 15 people

No registration required.

-

Events and Receptions

- Sunday, June 23

- Monday, June 24

- Tuesday, June 25

- Wednesday, June 26

- Thursday, June 27

- Friday, June 28

-

Opening Ceremony

16:00

Auditorium Lumière, Centre des Congrès de Lyon -

Opening Cocktail

19:00

Auditorium Lumière, Centre des Congrès de Lyon

-

Doctorat honoris causa: Orhan Pamuk

Award ceremony of the title of Doctor Honoris Causa to Orhan Pamuk, Writer and Nobel Prize for Literature 2006

Grand Amphithéâtre - Palais Hirsch, Université Lumière Lyon 2

17:30

By invitation only

-

Lecture of Jacqueline Salmon at Musée d'art contemporain de Lyon

Du projet à l'objet - Matériaux à l'oeuvre

Précédent les projets : un mille-feuille, de choses vues, lues, entendues et mémorisées, de parts larges ou minimes, concrètes, découvertes, choisies, cadrées, prélevées dans le monde et rendues au monde, métamorphosées à l’aide d’actions nécessitant des outils précis.

Un exemple simple avant la photographie numérique : Lônes, 1989 photographies de paysages.

De l’idée à la réalisation, comment les matériaux intellectuels et matériels mènent l’œuvre en constante synergie. Liste et description des outils et des actions nécessaires, depuis la recherche du titre jusqu’ à la réalisation d’une exposition, d’une édition.

Un exemple complexe au temps du numérique : 42,84 km2 sous le ciel, portrait de ville. Interviennent des recherches en archives, des articles de journaux, des portraits, des plans urbains anciens et modernes, des statistiques, des dessins, des interviews, des vidéos, des ouvrages précis, des plans anciens, une nécessaire formation à la météorologie…

Suivi de la mise en œuvre avec la description des 8 outils numériques nécessaires.Auditorium du macLYON

11:00-12:00

Entry with Congress pass

-

Diner-performance of Daniel Spoerri at the Musée d'art contemporain de Lyon

Dinner-performance of Daniel Spoerri - Un coup de dés n’abolira jamais le hasard

From 19:30 -

Reception at the Musée des Beaux-arts de Lyon

Lecture, presentation of artworks and cocktail reception [19.00-22.30]

From 7.00pm: free visit to the exhibition Connecting worlds

7.15pm - 7.45pm: Lecture by Pierre Rosenberg in front of the artworks of Nicolas Poussin

Subject to registration (40 people).7.45pm - 8.15pm: Presentations of artworks by their restorers

- Antique sculptures

- Graphic art cabinet

- 19th century room Clémence de Sermezy

- Zurbaran restoration workshop

- Macau embroidery exhibition.

Each presentation is subject to registration (20 people per presentation).

8.30pm: Cocktail receptioni the Cloister Garden

9.00pm: Closing of the exhibition space10.30pm: End of the receptionWith the support of Cercle Poussin and Cercle 21, circles of individual patrons of Lyon's art museums.

-

Lecture of Gilles Clément & Coloco at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Lyon

Organised by the Musée d'art contemporain de Lyon and Archopel, the maison de l'architecture de Lyon

Depuis que la crise environnementale mondiale a radicalement changé l'approche des projets, nous sommes poussés à inventer de nouvelles stratégies. Immergés dans le jardin Planétaire, au sein du Vivant, nous cherchons à développer le projet en termes de temps au-delà de la création spatiale. La Préséance du Vivant propose une façon d'explorer les dimensions collaboratives et les méthodologies pour s'intégrer dans les dynamiques du Vivant. Cette opportunité de partager notre travail à Lyon avec cette exposition vise à réfléchir collectivement à notre responsabilité en tant que paysagistes pour façonner de nouveaux futurs.

« L’avenir sera fait de métissages naturels, culturels et technologiques imprévisibles. Nous devons repenser la place de l’espèce humaine au sein du vivant avec une responsabilité d’invention face à l’enjeu de préserver l’habitabilité de la planète. La nature n’est pas un état idéal, nostalgique d’un passé idéalisé, mais une force de renouvellement à comprendre avant d'intervenir sur un projet. À chaque situation ses réponses concrètes, toujours collectives et engagées durablement. »

Lecture on the occasion of the exhibition at the Orangerie du Parc de la tête d'Or

Auditorium du macLYON

18:30

Registration needed [full]

-

Reception organised by the École du Louvre at the Lyon Fine Arts Museum

Reception organised for all delegates who have received a mobility grant under various support programmes, in the context of their participation to the 36th CIHA Congress.

19:00

By invitation only.

-

Private evening organized by the Getty Foundation

19:30-21:30

By invitation only -

Private visit and cocktail reception at the Musée l'Organe - La Demeure du Chaos / Abode of Chaos

17:30/19:30 - 22:30/0:00

Guided tour of the 6,300 works that form the Demeure du Chaos / Abode of Chaos corpus, discovery of the world headquarters of Artprice by artmarket, the world leader in art market information, its historical documentary collection of catalogues and manuscripts from 1700 to the present day, cocktail reception and time for discussion with Thierry Ehrmann, sculptor and visual artist, author of the 6,300 works that form the Demeure du Chaos corpus and founding Chairman of Artprice.

Continuous tours throughout the evening.

Cocktails from 8pm.Free event reserved exclusively for the 36th CIHA Congress delegates, on presentation of access badge.

Registration subject to availability. Registration is closed.

Transport to and from the Congress Centre, organised by the Musée l'Organe - La Demeure du Chaos / Abode of Chaos and Artprice by artmaket.

> Several departures planned between 17:30 and 19:30 (details to come)

> Return between 22:30 and 0:00

-

Closing Ceremony

17:30-18:00

Auditorium Lumière, Centre des Congrès de Lyon -

Party ath the Musée d'art contemporain de Lyon

From 19:00

Late-night opening of the Musée d'art contemporain de Lyon

- Exhibitions open until 11pm

> Disorders – Excerpts from the collection Antoine de Galbert

> Sylvie Selig - River of no Return

> Works from the British Council and the macLYON collections : Friends in Love and War — L’Éloge des meilleur·es ennemi·es

> 40 years of macLYON - A look back in images- Party at the macBar, the Musée d'art contemporain de Lyon's bar. DJ set. Access to the terrace.

Free entry. Drinks not included.